Painting with Electrons: Book Cover Artwork

filed in Book Cover Illustrations and Artwork, Digital Painting on Feb.04, 2011

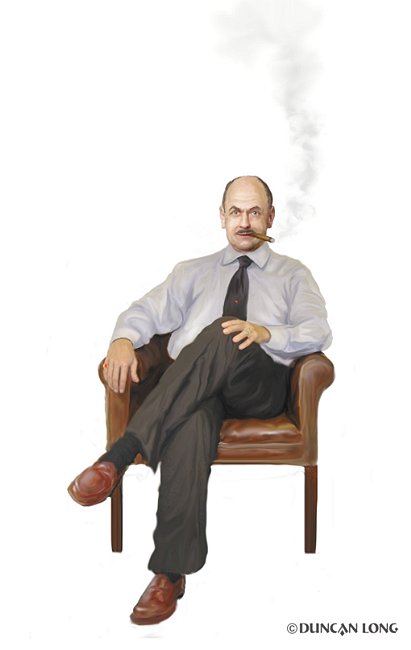

Although I used to work in oil paints and pen and ink, today my illustrations (like the one above for George Blackburne’s The Reverse Multiplier Effect) are all digital, painted by pushing electrons across the screen with a Wacom digital tablet and pen.

The sizes of the paintings I create for book covers are generally not much larger than the final book cover will be – perhaps larger by a few inches to make getting the finer details into the picture a tad easier. But they’re not the huge oil paintings that book illustrators of the past made.

Of course on a computer screen they seem large and detailed. That’s because most monitors show picture at 72 to 96 dpi (dots per inch) while print is generally created at 300 dpi. So basically there’s three times as much detail as in the picture above with the “paintings” I create digitally. But they still aren’t as large as one would expect. And, yes, I do miss the smell of oil paints; can’t reproduce that by pushing electrons.

By way of software, about 99 percent of my work is on an ancient version of Corel PhotoPaint. I’ve customized the keyboard commands and also have pen gestures to pull up often-used plugins, so do most of my work without having to fiddle with sliders or icons to change brush size, change from one tool to the other, and so forth — much, much faster.

The other plus of PhotoPaint is that I’ve worked with the same version of the program (Version 8 — the newest is 14, I think) for about 10 years now, so I know the thing by heart (including some of the glitches that Corel never fixed) — I can almost think it and the picture is done.

Well — just about (ha).

But no fussing with the commands or program. Just free to think and explore as I work.

On the downside, PhotoPaint is not industry standard and not really designed as a painting tool. So for those starting out, I recommend Photoshop or Corel Painter just to avoid compatibility problems on projects — as well as to land a job since many employers require Photoshop know-how.

But for a rebellious freelancer like me… I wouldn’t work with anything else.

=====================

When not crowing on his blog about the work he does, Duncan Long pushes electrons to create magazine and book illustrations and artwork for HarperCollins, PS Publishing, Pocket Books, Solomon Press, Fort Ross, ISFiC Press, and many other presses and self-publishing authors. You can find more of his book illustrations and artwork at: http://DuncanLong.com/art.html

=====================

February 5th, 2011 on 4:03 am

Interesting thoughts on your blog and marvelous illustrations. can i ask where you got your colors for these beautiful book covers from?

February 5th, 2011 on 4:57 am

Have to laugh @ your Corel PhotoPaint v 8 – mine is v 5 ! Invaluable!

February 5th, 2011 on 8:33 am

Version 6 – oh, my, someone has me beat in the old-timer contest. I went from 7 to 8 because of the feature that allows you to hold down a key and adjust the brush size of the tool you’re working with. I find that a valuable time saver that really, speeds up work. Were it not for that, I’d likely still be working on 7 — though I guess you’d still have me bet there.

The constant upgrade system many people engage in is very detrimental, I think. New programs invariably introduce new commands and layouts, so the craftsman never becomes accustomed to his tools. In effect, people are learning on the job, year after year. Only when you have been using the same program (or using the same tool) for many, many years do you start to become at home with it so that its commands become second nature. At that point you can pay attention to what you’re producing rather than what you need to do to make the program produce what you want to see.

I guess the bottom line is that most skilled craftsmen work with old tools they have owned for many years.

February 6th, 2011 on 4:50 am

This Quote I Love:The critical distinction between a craftsman and an expert is what happens after a sufficient level of expertise has been achieved. The expert will do everything she can to remain wedded to a single context, narrowing the scope of her learning, her practice, and her projects. The craftsman has the courage and humility to set aside her expertise and pick up an unfamiliar technology or learn a new domain. — Dave Hoover