Sometimes I’m contacted by writers having questions about how to translate a script or novel into a format that would allow an artist to create a graphic novel of the story. The process is not as straight-forward as one might imagine.

Many writers make the mistake of trying to put too much into each page and panel of a graphic novel. In theory a picture is worth a thousand words; in practice it is frozen in time. It becomes only a single snapshot incapable of covering more than one instant. It can’t convey time transitions that are easily covered in just a few words of text, and it will be lost completely when it comes to conveying abstract ideas.

One solution to this, and one the graphic novel is suited to, is having a large text panel cover the wider time spread. For example, “It had taken 300 years for the Glaxians to transform their economy from one of agriculture to industry, and finally into high technology. Now with the invention of the star drive, they were finally ready to venture into deep space.” This brief block of print would allow a panel showing a farm scene, one of early industry, and finally a large panel of a spaceship gleaming on its platform. It basically sets up the story that will follow, and tells us it will likely be science fiction about some culture unlike any on Earth (or possibly far in our future). The text gives a wide view of history and then the pictures three snapshots within that spread.

But the three illustrations by themselves would fail to tell a clear story. They might be interpreted as three different places on the planet, three different worlds, or three times in history — any reader’s guess without the carefully crafted pair of sentences (and don’t kid yourself, carefully crafted short sentences can be harder to write than several pages of text).

So what should a graphic novel script look like? What does an illustrator need to create the right pictures for the storyline?

Here are some good panel layout scripts (probably you’d need to add some word panels to the mix for a graphic novel — these scripts are for conventional comics): The Souls of Cyber Folk, The Man In The Machine and Icon 13.

These panel scripts may be expanded into a fuller script like this to give the writer more complete control over his story: Overture.

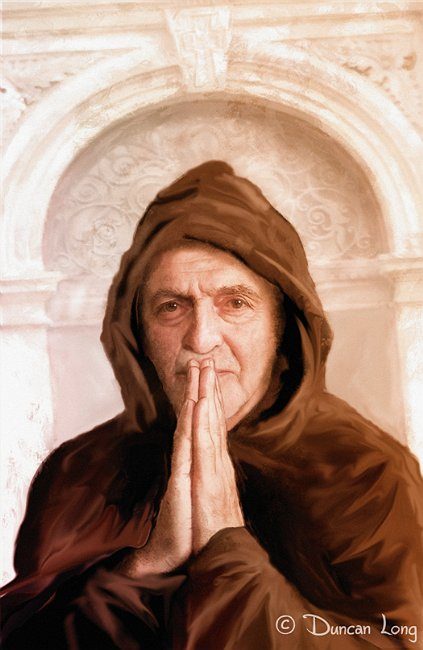

Such scripts are the most ideal way to go. However, there are other possibilities. You might, for example, lean more toward the novel and less toward the graphics side of the graphic novel. This was the basic solution that John Chadwell and I employed for our upcoming The Werewolves of New Idria (Moonstone Books). We had one page of text from his story, and one illustration for the key scene within that page of text. That worked quite well for his story and allowed for very expansive, almost cinemagraphic look for the illustrations. It isn’t the solution for every story, but it worked well for the one John had written.

A book or script needs to be very carefully plotted out, edited, and perhaps simplified to yield the type of scenes that would work in a graphic novel. It’s a tricky business and likely the reason more scripts don’t make an easy transition into graphic novels (while graphic novels are more easily made into movies).

Many writers also wonder about the costs of hiring an illustrator to do the artwork for a graphic novel. The key thing to remember is that the artist will generally spend a lot more time in creating a page of the graphic novel than the writer will in writing it; additionally he’s invested a good part of his life honing skills, generally with little or no pay during that time. All this means he will expect to earn a little more than the writer does when he signs on to do a graphic novel.

For this reason, when a graphic novel is published by a press, the royalties paid to the artist will normally be twice as much as for the writer (or if there’s a penciler and an inker doing the artwork, they will each get the same amount as does the writer).

If a writer wishes to hire an illustrator to do the illustrations for a graphic novel that will be self publish, the payment for his work will of course depend a lot on his experience. For quality work, $450 to $1,000 per page of black and white (or grayscale) artwork and a bit more for color pages is typical. The cover for a graphic novel will cost around $1,300 for a quality illustration.

When a writer hires an illustrator up front, generally no royalties are paid when the graphic novel goes into print. That’s good for the writer if lots of sales are made; good for the artist if sales are meager. (Of course any arrangement for payments can be made, from all royalties, to all payment for the work and no royalties, to some sort of split between the two. Generally it is best not to enter an agreement that involves giving away the firstborn of the writer.)

Often a professional artist will ask for half the payment up front before starting his work, with the balance upon completion. That protects him from fly-by-night operators but also means a writer or publisher needs to choose an illustrator that’s trustworthy and has the talent to do a good job with the work. Otherwise a lot of money may be spent without much to show for it.

Because graphic novels can make a lot of money, especially if the story later becomes a movie, it’s wise to have a contract that spells out who does what and how payments will be made, who gets royalties and what they get them for, etc., etc. A contract can save a lot of headaches, hurt feelings, and even lawsuits. Don’t work without one, and never work with someone who refuses to do so.

====================

Duncan Long created the illustrations for John Chadwell’s story The Werewolves of New Idria. You can view more illustrations from this graphic novel at the The Werewolves of New Idria gallery.

You can also view other artwork by the artist at Duncan Long’s Book Cover Portfolio.

=====================